WHY IS GOOD HYGIENE SO IMPORTANT?

Hygiene promotes wellness – physical and mental

Hygiene for physical health

No one likes to be sick. You feel yuck. You can’t enjoy your normal activities. And you might not be able to work and earn income. Illness also costs the Australian economy billions in health expenditure and lost productivity.

Good personal and home hygiene help reduce the spread of infectious diseases such as colds, flu and gastro.

In Australia we have pretty good public hygiene measures, like safe water, removal of waste garbage and sewage. Improvements in living conditions have also played a huge part in decreasing infectious disease. Australian regulations also help ensure good hygiene practices in commercial establishments, as well as in manufacturing and agriculture.

Hygiene for mental health

The importance of good mental health cannot be underestimated. Good hygiene can help you feel good in your own skin, giving you confidence, assisting your social interactions and helping you be engaged and productive in all areas of life. Good hygiene also helps to make your home, and the public areas you visit, comfortable and welcoming environments.

Good hygiene would not be possible without high quality, effective hygiene products, as well as good hygiene practices.

WHY IS GOOD HYGIENE SO IMPORTANT?

How does hygiene prevent the spread of infectious disease?

Today, common infectious diseases in Australia include gastrointestinal diseases, colds and flu. In the past, diseases such as polio, measles, tuberculosis, scarlet fever and whooping cough claimed many lives. Many of these diseases still cause death, incapacity and suffering in developing countries.

How are infectious diseases transmitted?

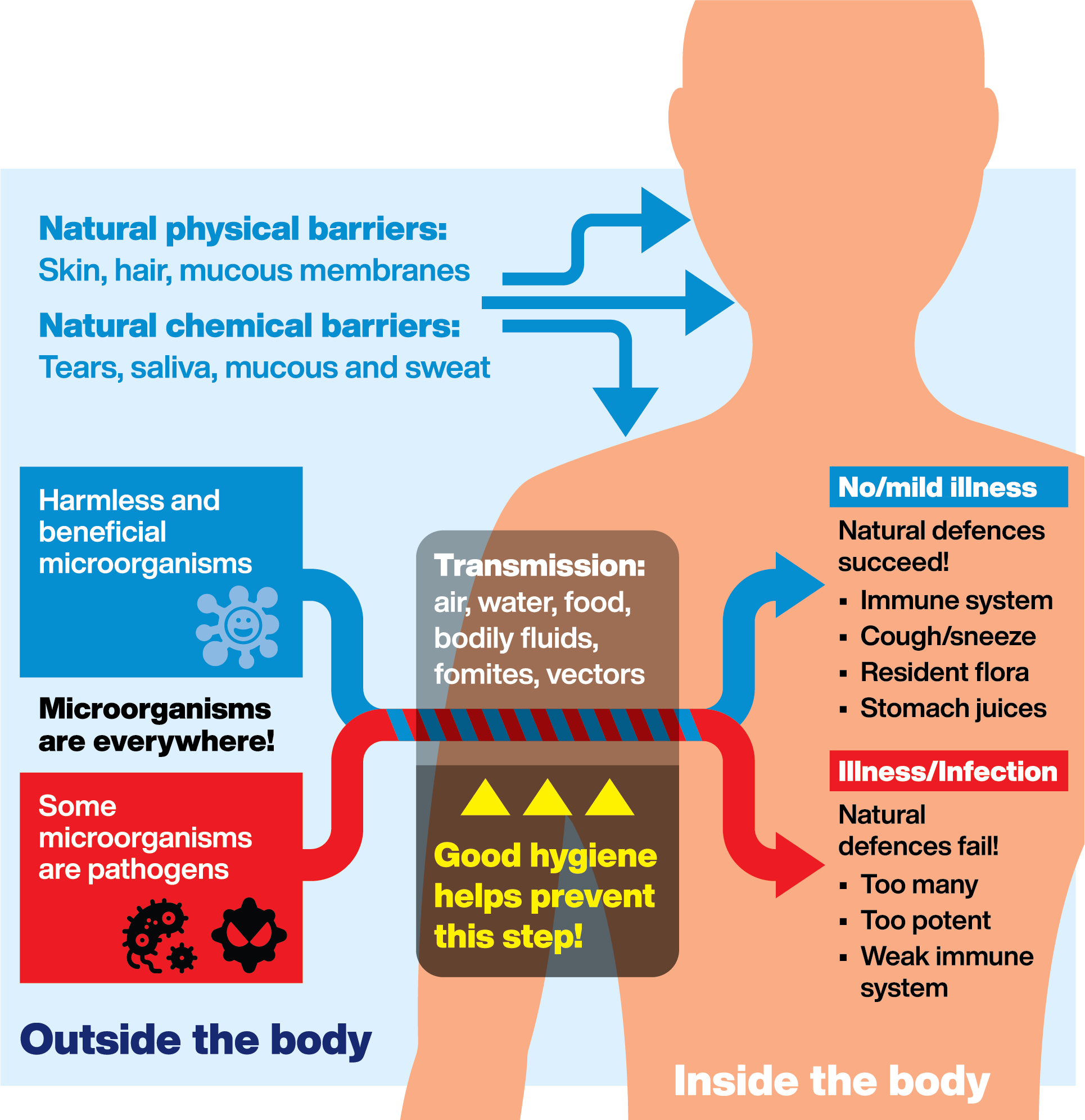

Infectious disease can occur when disease-causing microorganisms (‘pathogens’), enter your body. Not all microorganisms are pathogens. In fact, most microorganisms you encounter on a daily basis are harmless, while others play a key role in keeping you healthy.

Pathogens can cause illness in several ways. They can release poisons into the body, prevent cells from performing their normal functions, or multiply rapidly and so prevent normal organ function.

Pathogens can be spread via:

Water: Untreated or inadequately treated water is responsible for approximately 80% of all illnesses and deaths in the developing world.[iii]

Air: Aerosols from coughs and sneezes can travel on air currents and be inhaled.

Direct contact with bodily fluid: Droplets of blood, respiratory tract fluid (dispersed by coughs, sneezes or talking) or sexual contact can transmit pathogens.

Food: Eating contaminated food can cause ingestion of pathogens.

Inanimate objects (‘fomites’): Indirect transmission can occur via objects such as phones, surfaces, door knobs, writing utensils and medical equipment.

Vectors: Living organisms can transfer pathogens from one host to another, e.g. fleas pass microorganisms from the blood of one host to another as they bite

But your body is not defenceless!

Physical barriers such as skin, hair and mucus membranes help prevent foreign microorganisms from entering your body.

Your immune system can recognise and destroy foreign microorganisms.

Chemical defences such as saliva, sweat, tears, mucous and stomach acid can destroy microorganisms.

Resident flora (‘good’ bacteria) live in your body and help fight other microorganisms.

Coughing and sneezing expel microorganisms from your lungs.

Vaccinations provide protection from many infectious diseases.

However! These defences can fail if pathogens are too numerous or too potent. Or the body’s natural defences may be weak. For example, people who are very young, very old, undergoing chemotherapy or suffering from AIDS generally have weak immune systems. Broken skin can also allow pathogens to enter the body.

Good hygiene is important because it prevents pathogens from entering your body in the first place.

Effective hygiene practices and proper use of quality products are essential to maintain good standards of personal, home, public and industrial hygiene.

WHY IS GOOD HYGIENE SO IMPORTANT?

Is it possible to be too clean?

The ‘hygiene hypothesis’ was first proposed in 1989. It suggests that being too clean could be responsible for the observed increase in allergies and autoimmune diseases in developed countries over the last century. These disorders remain rare in developing nations, where life-threatening infectious diseases remain common.

Allergies occur when your immune system overreacts to allergens in the environment, or in certain foods (e.g. peanuts) and toxins (e.g. bee stings). Drugs can also trigger an allergic reaction. Symptoms range from mild swelling, watery eyes and sneezing to life-threatening anaphylaxis.

Proponents of the hygiene hypothesis believe that exposure to a variety of microorganisms early in life teaches the immune system how to react to foreign substances. The theory goes that when young children grow up in ‘sterile’ environments their exposure to harmless and beneficial microorganisms as well as to pathogens is reduced.

Supposing this hypothesis to be true, it still needs to be put in perspective.

As infectious disease expert Dr Michael Bell puts it, ‘Living more sanitarily may have increased asthma, but in terms of scale and impact, that’s tiny compared with the benefit of not dying from disease for lack of hygiene.’[viii]

Indeed, deaths from infectious diseases have declined by over 96% in the past century in Australia.[ix]

Common sense and moderation are needed. Practise and teach good personal hygiene, clean your home well – particularly areas like the bathroom and the kitchen – but don’t cloister children from all dirt. Use antibacterial cleaners in areas and situations where they are most needed, and of course the strictest infection control practices must still be followed in health care settings and food production facilities.

[i] Medibank, KPMG Econtech, 2011, Sick at work: The cost of presenteeism to your business and the economy.

[ii] National Institutes of Health, 2012, ‘NIH Human Microbiome Project defines normal bacterial makeup of the body’. Accessed 4/1/2019

[iii] UN Press Release, 5 June 2003, ‘Water-related diseases responsible for 80 per cent of all illnesses, deaths in developing world’, says Secretary General in Environment Day message.

[iv] National Health Service, 2015, ‘How long do bacteria and viruses live outside the body?’. Accessed 4/1/2019

[v] American Society for Microbiology, September 8, 2014, ‘How quickly viruses can contaminate buildings – from just a single doorknob’. ScienceDaily. Accessed 4/1/2019

[vi] Fenollar, F. & Mediannikov, O. (2018). ‘Emerging infectious diseases in Africa in the 21st century’, New Microbes and New Infections, 26, S10–S18.

[vii] Australian Bureau of Statistics, 2018, 3303.0 Causes of death, Australia, 2017.

[viii] Wall Street Journal, 17 May 2010, “Can dirt do a little good?”.

[ix] AIHW, 2006, ‘Mortality over the twentieth century in Australia: Trends and patterns in major causes of death’, Mortality Surveillance Series no. 4. AIHW cat. no. PHE73.